open main page here

NATURAL COLOR CHANGES IN WOOD

INTRODUCTION

It is not my intent on this page to present an exhaustive list of the color changes in various woods but rather to show examples of the various KINDS of color changes that happen in woods.

Also, this intended as a cautionary tale for woodworkers. I used a lot of redheart in my early days of turning segmented bowls, not knowing that all the pieces in all the bowls would fade from a beautiful bright red to a bland dull brown. I also used osage orange for its bright yellow color, not knowing that all the pieces would change to brown over time. I though that UV-blocking finishing agents would inhibit any color change, but BOY was I wrong. Very disappointing. It is wise to be sure you understand the color properties of any wood you are working with before you start a project. I learned this the hard way, and I hope you don't have that disappointment.

There are numerous UNnatural ways to change the color of wood (paint, stain, dyes, fuming, etc) but this article is not intended to address any of them.

REASONS FOR NATURAL COLOR CHANGES IN WOOD

There are three basic reasons for color changes in wood

- rapid short-term chemical processes when the wood is first exposed to light and air and rapidly loses surface moisture

- long term exposure to UV radiation (sunlight)

- long term exposure to oxygen

When wood is first exposed (the log is cut open), the wood is wet but it rapidly loses surface moisture (retaining internal moisture for much longer) and just that alone can cause a significant change in color in the very short term (hours / days). It also has its first reaction to oxygen and this first exposure can have a stronger effect than the additional effect that you see over more time. These changes in the wood when it is first exposed usually happen fairly early on and are over with by the time a woodworker has a dried piece of lumber ready for use in a project. I think this is primarily a destruction of pigments due to drying out and oxidation, but I don't know much about this process, it's just something that I've seen physical examples of.

UV radiation, particularly if accompanied by exposure to wind and rain over a period of months or years, will turn almost any unprotected piece of wood silver gray by breaking down the pigments in the wood, but with finishing agents and limited exposure to direct sunlight, few woods go that far and some hardly change at all. There are finishing agents (polyurethane for example) that contain an ultra-violet blocker, but these only slow the process of color change in the wood, as is demonstrated in some of the examples on this page. With some exceptions, UV is the primary cause of significant color change in all woods and the only way to prevent such change over time is to put the wood in a sealed closet and never open the door.

Exposure to oxygen causes oxidation in the surface of the wood. "Oxygen causes oxidation" is redundant, but I state it that way because everyone is familiar with the effects of oxidation on steel. It's called rust. Oxidation doesn't have as extreme an effect on wood as it does on steel, but oxidation is very real and does cause color changes in some woods, usually a fading of the color. Unlike the effects of UV exposure, oxidation CAN be pretty much eliminated by putting on enough coats of a finishing agent such as shellac or polyurethane that completely blocks oxygen from getting to the surface of the wood. That often is not all that helpful on many woods because the effects of UV (even very indirect sunlight over a long enough period of time) are much more severe than those of oxidation. Rub-on oil based finishes are totally ineffectual over time in blocking color change. Also, a coat or two often won't have much effect. See the purpleheart turning down in the "severe darkening" section.

I have it anecdotally that boiling some woods (madrone was mentioned) will retard color loss. Other reports say that boiling will leach out some of the color but pressure cooking will stabilize it more.

THE EXTENT OF COLOR CHANGES

Most color changes in wood go all the way through the wood (I'm assuming here a craft sized plank, not a large log) but some seem to be only "skin deep" and can be sanded off. I think that depends on age. Really old pieces are not likely to have only a surface change in color. For example, the piece of pistachio shown under "severe darkening" below had what was clearly only a skin-deep patina of dark color that sanded off fairly readily. This piece was only a couple of years old (possibly less) so I don't know how far down it goes over time. I've had other woods where the patina went down perhaps 1/16 to 1/8 inch but the color change on those had only been happening for a few years.

Here's an example of a color change that is penetrating fairly quickly:

On the left is a piece of sapodilla, which is is a very pretty pink when freshly cut but builds up a fairly thick patina of dark color within months and within a few years the color change has penetrated at least 1/2 inch to 1 inch into the wood. This piece is a few years old and still shows some dark pink in the middle (that was originally a lighter pink). It was sliced from a wider plank, thus the pink in the middle of the right edge, vs the darkening deep into the left edge (as seen in the end grain).

On the right is a bookmatch pair of edge grain surfaces from pieces sliced from a plank of paela that was only a couple of years old (and only 3/4 inches thick). After a few more years, the dark color will penetrate all the way into the wood. The color change in palea is often, but not always, uniform as the wood darkens internally. This pic is of a piece that clearly is not changing color uniformly. Given enough time, I expect that the whole piece will become pretty much uniformly the same as the darkest areas that are in it when this pic was taken.

GOOD COLOR CHANGES

I don't have any pics to post, but some color changes in wood are for the better. The most striking example of this that I can think of is in American black cherry. This wood takes on a gorgeous golden-brown tone over time that is considerably more attractive that the wood in its raw state.

Another is genuine mahogany which takes on a very deep rich tone after years of proper treatment (which includes frequent polishing in the early days).

Many species of oak will, over time, undergo a very moderate color change that slightly deepens and enriches the color.

VERY SHORT TERM COLOR CHANGES

Immediately upon being milled, there are some woods that have a color that fades or otherwise changes very quickly due to chemical changes in the wood as it looses surface moisture and becomes exposed to oxygen. In a matter of days, or even hours, the original color is gone, or seriously changed, most commonly fading to a more dull color. Because this happens well before the wood is dried and ready for any kind of use, the original color is not something normally associated with the wood.

An excellent example of this is sycamore. Some sycamores (not all, as I understand it) are a nice pink, sometimes even verging on red, when fresh cut but within days that fades severely. Here is a pic of a particularly strong example of that.

this shows 3 different pieces of sycamore: an unusually dark pinkish and red fresh-cut slab, a different fresh-cut slab with a more normal light pink color, and a dried plank from another log. The owner of the dark piece told me that the sapwood faded to the color of the middle piece and then to something like the dried plank shown. He did not comment on the color change in the heartwood, but I assume that it turned brown over time. I did not get the specific times involved but my belief is that the initial fading was days and the further fading was probably weeks if not more. The middle slab's sapwood would also fade to the color of the plank on the right, or possibly even a more of a white color, and the heartwood to a light brown.

Clearly, if you get a piece of sycamore that has a strong pink color or even is reddish, it is fairly freshly milled and needs to be dried before use and the color will fade.

VERY SEVERE COLOR CHANGES

There are a few woods that go through really radical changes in color over time. One of these is osage orange, which starts out freshly cut as a brilliant yellow and over time changes to a deep chocolate brown. I have also been told that it sometimes changes to a dark red but I have not experienced that myself.

the top section of a segmented spittoon-shaped turning that I did. The pic on the left is after several coats of UV-blocking polyurethane and the pic on the right is after it sat on a shelf in natural light (very indirect sunlight) for about 8 years. The UV-blocking finish slowed the change in the color but could not prevent it.

Another of my favorite woods, that has a very unfortunate color change over time is padauk, which changes from a brilliant red to a bland brown.

padauk plank that was partically exposed to sunlight for a couple of years and clearly shows how the red turns to brown. The red areas were a slightly brighter red when I got the plank.

MODERATE COLOR CHANGES

Some woods change color like osage orange, but less radically. One example of this is mulberry, which starts out almost as bright as osage orange and over time turns to what I've seen several times described (accurately) as a "warm brown" (as opposed to the deep brown that osage goes to).

a mulberry segment on a bowl I made. On the left is the freshly finished bowl (10 coats of UV-blocking polyurethane) and on the right is the same bowl after a few years in indirect sunlight.

Many woods that change color have brown as the final color, so here's another example. Bulletwood starts out as a dull red but over time changes to brown:

This is a small piece of bulletwood that I did a color exposure series on. The pic on the left is the piece fresh (actually, I think it had already started to turn a bit by the time I got it) and on the right is the same piece after it was exposed to direct sunlight for a an hour or two and indirect sunlight for the rest of the day, over a period of 4 months.

A piece of Eastern redbud that was partially exposed to sunlight, partially covered by another plank. As you can see, the greenish tint changes to tan and the area exposed to sunlight darkens to a deeper brown than the covered area.

Purpleheart is a wood that ranges from moderate to severe depending on the piece. First, "purpleheart" is a trade name for at least 20 species in the genus Peltogyne and in addition to diferences due to species there are also differences due to soil conditions in the area of growth. Most pieces start as a brownish purple and the purple color becomes richer with exposure to UV and oxygen, but in some species the starting color is closer to purple and it turns brownish. Some pieces will take on a dark patina that is nearly black with enough exposure, but you don't often see that --- I do have something fairly close though; look at the purpleheart turning under "severe darkening" below.

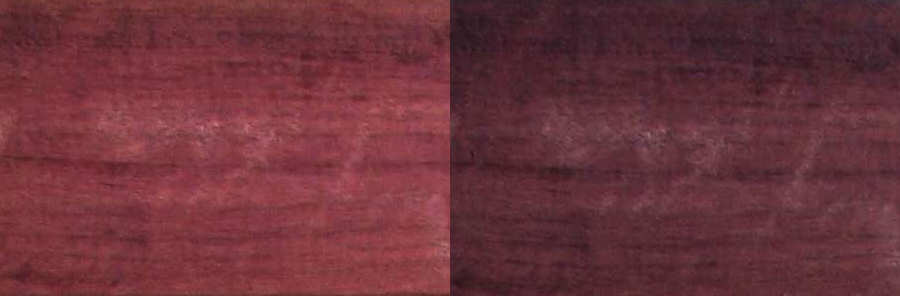

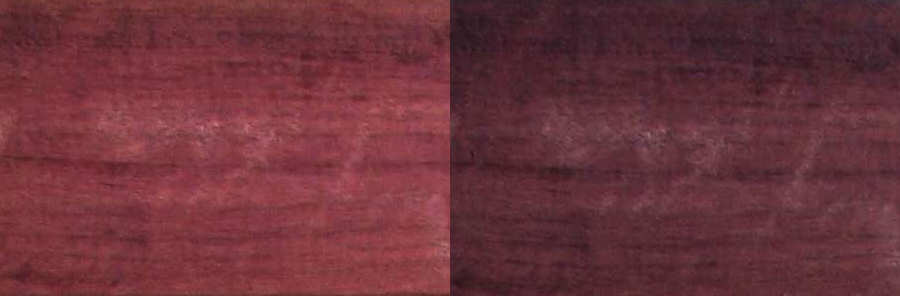

This is a section of a piece of purpleheart that may have started off more brownish but was a nice light purple when I got it. On this piece I have accelerated the normal change from one purple (shown on the left) to a darker purple (shown on the right) by cooking the plank for an hour at 300 degrees. This process is discussed more on the purpleheart page of this site, which also shows some of the various colors that are found in purpleheart.

SEVERE FADING

Some woods fade severly with exposure to UV. The saddest of these, to my mind, is aromatic red cedar. I don't have any examples to post, but I've used this wood a lot and it is disheartening to see it go from the vibrant, brilliant purlish color when first cut to a faded, dull brown. UV is an absolute killer on that wood. With a good UV-blocking finish, it will keep some of the redness instead of going to pure brown but it will totally lose the brilliant purple color. Another one is box elder, which CAN be (but isn't always) be suffused with beautiful red streaks that sadly fade over time to a dull pink.

Another of these is redheart.

A section of a small piece of not very attractive to start with redheart on which I did a color exposure series. The first pic is the raw piece and the second one is after it was exposed to direct sunlight for a an hour or two and indirect sunlight for the rest of the day, over a period of 3 months. Although this piece of redheart is nowhere near as pretty as some I've had, it really doesn't matter in the long run because they all end up this way.

And another is the flame color in box elder. This is a bowl I made and then the same bowl after several years of daily exposure to strong indirect sunlight. It's finished with about 10 coats of UV-blocking polyurethane, but that just slowed down the fading a bit.

SEVERE DARKENING

Some woods darken severly over time, mostly through exposure to UV. This darkening doesn't change the color so much as just darkens it, although it some woods the process does remove much of the original color and move the color towards black, not just a darker shade of the original color. Among these are cocobolo, bocote, purpleheart, bloodwood, and others.

Here are some examples of bloodwood and bocote.

This is the first bowl that I ever turned. The bloodwood piece that I used was a very rich red but after many years of sitting on a shelf in indirect sunlight, it darked quite a lot but is still identifiably red. The underside of the bowl darkened slightly but is much closer to the original color.

The bloodwood base of this pedestal bowl turned almost black over time, despite 10 coats of UV-blocking polyurethane.

The pic on the right is of the bottom of a bobbin holder (thus the dowel pins) that I made for my wife out of a piece of bocote that came from the other end of the plank shown in raw form on the left. The bobbin holder was finished with a coat of tung oil and exposed to oxygen and indirect sunlight for about 6 years. The dark lines stayed pretty much the same but the nice golden color darkened to what in a bright light (such as for this pic) is a chocolate brown and which in natural light looks almost black.

On the right is a piece of aged pistachio as I received it. On the left is the same piece after I sanded off the patina of dark wood and got back to the raw color.

This is a purpleheart sample turning I did and then stuck away in a closed cardboard box for about 9 years and when I found it again after all that time, it had darkened as shown. Since it was in the box for almost the entire 9 years, this darkening clearly has to be from oxidation even though it had a couple of coats of polyurethane.

This is a bowl made of African sumac and aged for a few years, shown with a piece of identical, but freshly milled wood, sitting in the middle. This pic was provided by Barry Richardson, whom I thank for the contribution.

APPARENT COLOR CHANGES

Some woods are what is called "chatoyant", which means that they take on a significantly different look depending on how the light hits them. Here is an example of that:

Two different views of a segmented oak bowl (the red stripe is padauk veneer). These pics were taken under identical lighting conditions, just from different angles. You really have to look at the pics for a minute to realize that they are indeed pics of the exact same area of the bowl, it's just that the change in angle of the light causes a radically different look to both the normal area of the wood (which goes from whitish to yellowish in moving from the left pic to the right pic) and the rays (which go from dark to light in moving from the left pic to the right pic).

Some woods take on a distinct shimmer when looked at from one angle vs another, and the surface of the wood can seem to dance before your eyes as you move the wood through diffent angles. You can't tell it from this still pic, but here's an example of a piece of sipo with a polyurethane finish that exhibits this characteristic:

chatoyant sipo